Is the World’s Best Figure Skater another Example of Russian Doping or an Innocent Victim of Contamination?

By Oliver Catlin

Halfway through and the 2022 Beijing Olympics are spinning thanks to the latest Russian doping affair surrounding the world’s best figure skater. The future of the Olympic movement now hangs in the balance. This is the last thing the Olympic movement needed after the worst doping scandal ever perpetrated during the 2014 Sochi Olympics. It is easy to have a knee jerk reaction to the current case, where 15-year old figure skating sensation, Kamila Valieva, tested positive for the drug trimetazidine on a Christmas Day drug test that was finally reported on February 7. Now the entire Olympics awaits a decision to be made this weekend after the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) was called in to sort out the matter. Most people probably think she is a doper given the scandalous history in Russia, but as we have learned over our years in anti-doping the answer may not be that straight forward in the end.

Let’s start with what trimetazidine is so we can get a foundation. Trimetazidine (TMZ) is a heart medication that has been used in medical practice to treat angina or stroke. It is not approved for use in the U.S. One paper describes that as an “orally administered antianginal agent trimetazidine increases cell tolerance to ischaemia by maintaining cellular homeostasis.” In simple terms TMZ can increase blood flow and stabilize blood pressure and can have endurance benefits. In 2012 the European Medicines Agency, “recommended restricting the use of trimetazidine-containing medicines in the treatment of patients with angina pectoris to second-line, add-on therapy.” It is banned in sport as a metabolic modulator in category S4.4 alongside another now infamous doping agent meldonium, also an anti-ischemic agent. Overall, the WADA system reported 57 trimetazidine findings from 2014 when it was first banned to 2020.

To most people it would seem unlikely that Valieva has a heart condition at age 15 that would justify medical use of TMZ. It is now recommended only as a second line therapy perhaps making legitimate treatment even less likely. Even if there was a medical need if she didn’t get a therapeutic use exemption (TUE) and disclose the use of TMZ in advance that would be a violation in itself.

The Valieva situation is framed by several trimetazidine cases. Sun Yang, the Chinese swimmer now notorious for a string of doping concerns, tested positive for trimetazidine in 2014. Yang claimed he had been prescribed it for chest pains but he did not declare it on his collection form. Yang received a three-month ban, his Chinese doctor was banned for a year. Valieva joins fellow Russian bobsledder Nadezhda Sergeeva who tested positive for trimetazidine two days prior to her race and was banned from competition at the 2018 Pyeongchang Olympics. Sergeeva served an eight-month ban after it was considered that she had used a contaminated supplement.

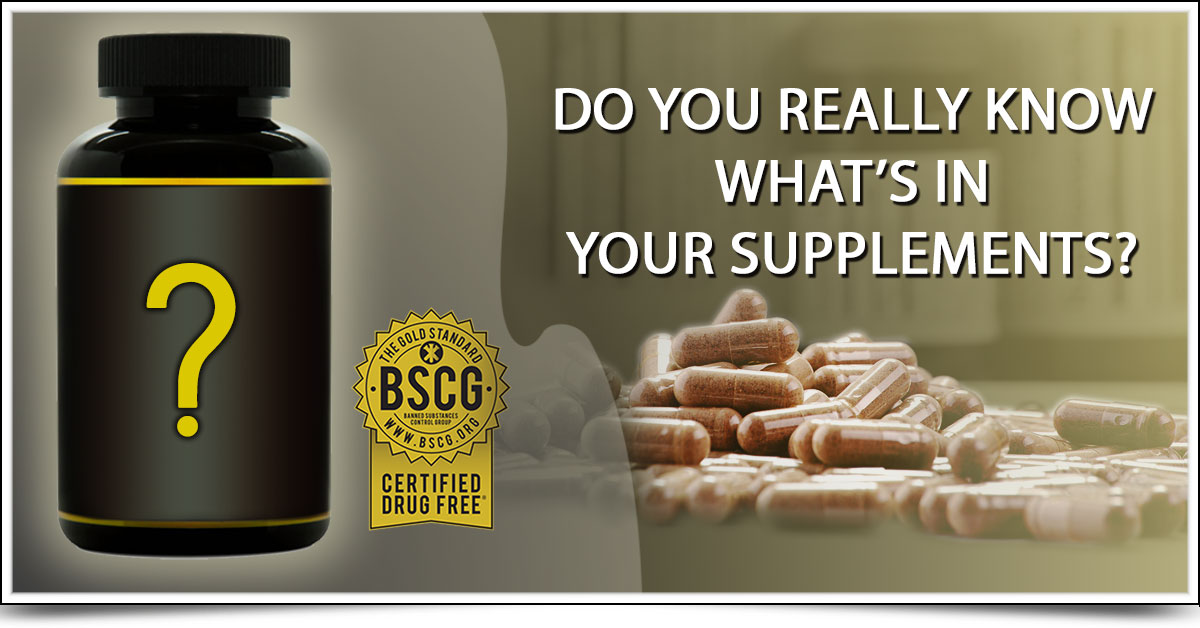

A third case in 2018 also points to the concern of supplement contamination. U.S. swimmer Madisyn Cox was positive for trimetazidine and originally thought it had come from water contamination. Cox eventually had her sanction reduced to six-months after testing discovered TMZ as a contaminant in a supplement. At BSCG our business revolves around protecting athletes from nutritional supplement contamination through our industry leading Certified Drug Free program, which verifies supplements are free of banned substances. These cases illustrate how important it is for athletes to protect themselves from the risks of supplement contamination.

Sergeeva’s is an illustrative case when it comes to the timeframe of action as she was banned from the Olympics two days after testing positive. Yet we still have no answer on Valieva? It is now five days past the result being announced, 49 days since the sample was taken, and we still don’t have an answer? This stinks of politicking to us, and surely many others.

Why did six weeks pass before a final result was issued? The laboratory in Sweden that did the testing explained the confirmation of the result was delayed due to COVID issues, something we can sympathize with and understand. We don’t believe anything nefarious happened at the lab. This isn’t a lab issue unlike the debacle in Sochi.

In a powerful article, Yahoo Sports reported that the Russian Anti-Doping Agency (RUSADA) evaluated the Valieva situation and decided on February 8 to issue a provisional suspension. Then in classic fashion RUSADA turned around the next day and overturned it with no reason provided, clearly heightening suspicion. The Russian Olympic Committee released a statement Friday saying she had “passed numerous doping tests” before and after Christmas Day.

Travis Tygart, head of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) is not happy. Surely there is another Russian doping fiasco afoot. In the Yahoo Sports article Tygart called the excuse, “classic diversion by the Russians.” Tygart goes on to say, “This drug doesn’t just show up in your water somehow, my guess is … there is likely someone else behind how she got this drug. Again, I don’t know the facts. But clearly you have enough to ask those kinds of questions and demand answers to them.”

We don’t know the facts either but the theories are flying. Could a rogue doctor or trainer have been responsible for giving her something? The Russians are investigating and I don’t think anyone would want to be one of the targets of that investigation. Looking for a scapegoat perhaps? There have certainly been cases where support personnel have doped athletes, both purposefully and accidentally.

Tygart’s comments to Yahoo Sports are quite interesting as they allude to another possible reason Valieva, or any other athlete for that matter, could test positive for trimetazidine or other drugs. That is contamination of food, prescription drugs, and yes maybe even water.

The research has actually proven that water, and even crops, could be contaminated with drugs banned in sport, even trimetazidine. A 2021 summary by Polish researchers explored the concern that pharmaceuticals may appear in water and pointed to 826.7 ng/L of trimetazidine that was found in raw wastewater in Poland with 457.8 ng/L in treated wastewater. Other banned substance categories like stimulants, hormones, diuretics and beta-blockers were also found in variety of water samples. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency poster presentation demonstrated how drugs banned in sport could infiltrate crops irrigated with treated wastewater. This highlights the unfortunate reality that not all drug residues are removed during water treatment and that irrigation with treated wastewater can result in contamination of crops.

I wrote an article on, “Differentiating adulteration from natural or environmental presence in dietary supplements,” for Natural Product Insider in late 2020. The article noted the many challenges we face with compounds banned in sport that surround us every day in items like whey protein, deer antler, plant extracts, or sometimes our water and food.

The possibility of contamination causing positive drug tests is well noted both in World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) regulations and also in prior doping cases that have established a precedent for innocent sources like meat to be considered a likely source of a positive. WADA has now accounted for meat contamination in a technical letter outlining, “Minimum Reporting Level for Certain Substances Known to be Potential Meat Contaminants.” The document explains special thresholds to avoid innocent positives from clenbuterol, ractopamine, zeranol and zilpaterol. But are those the only potential meat contaminants?

A patent application filed in 2016 for ‘Extended Release Formulation of Trimetazidine’ describes in the abstract that, “The present invention relates to a dry ready to use modified release dosage formulation for Trimetazidine dosage forms and its salts and derivatives thereof,… also use thereof as additive to animal feeds, foods and food supplements and also cosmetic and pharmaceutical compositions.” With use in animal feeds outlined this would seem to establish a possibility that trimetazidine could not only show up as a water contaminant in the environment but also as a possible meat contaminant.

Trenbolone is a commonly used anabolic steroid implant used in the livestock industry today and yet there are no thresholds to account for it as a possible meat contaminant. This was a primary concern in the case of Alex Wilson, a Swiss sprinter who tested positive in March of 2021 for epitrenbolone, a metabolite of trenbolone.

The Sports Integrity Initiative suggested a review of meat contamination was needed after the Swiss Olympic Federation was rebuked by WADA and the Athletics Integrity Unit of CAS for considering meat contamination in Wilson’s case and voiding a provisional sanction. The sanction was reinstated by CAS and it kept him out of the Tokyo Olympics. The article notes, “when trace amounts of known meat contaminants are involved and a proffered explanation has already been accepted as likely, it seems a little perverse for anti-doping to celebrate ending an athlete’s Olympic dream.”

Meanwhile, Carl Grove, a 90-year old American cyclist, set a world record in his age group in the Masters Track National Championships in 2018 only to test positive for the same drug epitrenbolone. USADA investigated and in their statement relieving him of any sanctions they noted, “Grove provided USADA with information which established that the source of his positive test was more likely than not caused by contaminated meat consumed the evening before competing on July 11, 2018. Prior to consuming the meat, Grove had tested negative for prohibited substances during an in-competition test on July 10, 2018.” Grove was allowed to keep his result and world record.

This crazy case prompted The New York Times to delve deeper in a 2019 review that included an interview with USADA’s Tygart. “Cases like this make us bang our head against the wall,” said Travis Tygart, the agency’s chief executive. “They’re not right.” He goes on, “I don’t think the meat industry has changed significantly,” Tygart said. “The issue is now that the labs can see so much farther down that the likelihood of capturing something increases.” In conclusion the article notes, “Tygart and Usada are pushing for changes when the World Anti-Doping Agency revises its rules in November. Tygart said he backed putting in minimums for some substances that don’t have them to help ensure that tests were not merely finding environmental contamination. He also said he believed that “no fault” cases, like when tainted food, water or medicine is ingested accidentally, should not be a violation or be publicly announced.” “It absolutely breaks my heart to see a case like this with Carl,” Tygart said.

The article notes a key fact, that any amount of a substance that has no thresholds, like epitrenbolone and trimetazidine, is a violation. “Usada is confident the positive test occurred because of the meat. Sophisticated modern testing methods showed that Grove had less than 500 picograms of trenbolone, “an extremely low level,” Tygart said. But there is no established legal minimum level of trenbolone; any amount is considered a positive.”

It appears that USADA made an exception to the rules in Grove’s case based on their investigation of the circumstances and the conclusion that the most likely reason Grove tested positive was innocent consumption of contaminated meat. Similar to what the Swiss Olympic Committee considered in Wilson’s case. Could similar reasoning be the reason why RUSADA overturned their initial provisional suspension of Valieva? Likely not since the RUSADA investigation appears to have only taken one day, but it is possible.

The case also highlights one of the challenges we face with the advancement of anti-doping testing capabilities. Today we can detect down to a fraction of a picogram (part per trillion) whereas a decade ago we were only able to see down to the low nanogram (parts per billion) level. With a thousand fold increase in the sensitivity of drug tests the timeframe of detection has drastically expanded. However, this also increases the possibility of finding miniscule amounts of substances that result from inadvertent and in many cases unavoidable ingestion of contaminated supplements or food.

Shelby Houlihan, one of America’s premier distance runners, tested positive for nandrolone metabolites before trials for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and is now serving a four year ban. Her case put the meat contamination concern in the spotlight in The Washington Post as she blamed the finding on a pork burrito she got from an Oregon food truck. The contention was rejected by CAS, hence the ban, despite research from the WADA community in 2020 that actually demonstrated the possibility that eating pork from random sources in Germany had a 16.7% chance of making a clean person test positive for up to 24 hours for nandrolone metabolites according to current WADA thresholds. That explanation was simply not believed in Houlihan’s case.

In 2019 The Athletic reviewed several low level positive drug tests in the UFC for Nate Diaz and Neil Magny noting that we live in a ‘contaminated world.’ Both Diaz and Magny had tested positive for tiny amounts of Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs) in the double digit picogram realm. When we say tiny we mean tiny, as in an amount equivalent to a grain of salt sliced into 50 million pieces then chopped in half. Both tested positive as a result of supplement contamination and they were relieved of any sanctions after investigation of the circumstances. Article excerpts below note some fascinating considerations that could be relevant in the Valieva case.

“Over-the-counter medicine and prescription medicine may have been contaminated for a long time, but we’re now picking them up,” said Dr. Daniel Eichner, head of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) accredited Sports Medicine Research and Testing Laboratory (SMRTL) in Salt Lake City.

Jeff Novitzky, the UFC’s senior vice president of athlete health and performance who works hand in glove with the promotion’s anti-doping program that is administered by the United States Anti-Doping Agency, believes the problem of contaminants is “getting worse and worse.” This is one reason the UFC’s anti-doping program will fully enact significant changes in the coming weeks.

Novitzky said in Los Angeles during a stakeholder meeting held by the California State Athletic Commission on Oct. 15 to address “common sense” disciplinary guidelines and minimum thresholds pertaining to certain prohibited substances. “But we have seen more and more commonly what I would call benign supplements being positive for prohibited substances. We’ve seen a couple of occasions where a women’s multivitamin having a SARM — ostarine — in it. We’ve seen creatine have prohibited substances. We’ve seen pure protein powder have prohibited substances. We’ve seen prescription medication from legitimate pharmacies be contaminated with prohibited substances. And we’ve seen contaminants at compounding pharmacies, both here in the U.S. and abroad where they’re mixing their own drugs and other drugs they’re mixing getting into a different drug.”

Of the approximately 13,000 individual tests that have been administered under the auspices of the UFC Anti-Doping Program since it began 2015, USADA and the UFC have announced sanctions on 100 athletes. A little fewer than half of them have come with “either definitive evidence or evidence tending to show that those positive tests were results of contaminants and not purposeful doping,” Novitzky told the California commission.

The UFC experience mirrors others with multi-vitamins, creatine, protein, medicine and other benign products often resulting in inadvertent positives. In nearly 50% of UFC doping cases investigations unearth an inadvertent source of the drug in question. This statistic was supported by John Ruger, U.S. Olympic Committee Athlete Ombudsman, who said, “between 40% to 60% of positive test doping results were inadvertent (non-deliberate) cases,” as quoted in a swimmingworldmagazine.com article in 2014. Imagine if that holds true across the spectrum of sport drug testing. So, did Valieva really dope or is it contamination? Flip your coin.

In a progressive move, the UFC now has reporting thresholds for SARMs set at 100 picograms and epitrenbolone set at 200 picograms. As of now, these thresholds only apply in the UFC anti-doping program and have not been adopted in the Olympic movement. There are no reporting thresholds for trimetazidine in the Olympic movement or elsewhere and any amount found is still a positive despite potential sources of contamination existing as noted herein.

Things are not always as simple as they may appear in the doping or anti-doping realms. There are many innocent and inadvertent reasons why an athlete could test positive. The problem is those same reasons also give accused athletes who really doped many excuses to point to other than cheating. Sadly, testing alone can’t distinguish between purposeful use that has faded away to miniscule levels over time and accidental use of something that could have been eaten or consumed yesterday.

Nonetheless, sprinter Sha’Carri Richardson tested positive for marijuana at the U.S. Olympic Trials just before Tokyo and lost her chance to compete at the Games while serving her one-month ban. Shouldn’t something like that have happened to Valieva? We are now at 49 days and counting since the positive sample was collected and Valieva is still on the ice with a possible gold medal in hand and likely more to come if she is allowed to continue in individual competition that starts Tuesday. That is simply outrageous regardless of whether she is the next poster child of Russian doping or an innocent victim of contamination called out by advancements in testing capabilities. Purposeful, accidental, or a mistake not declaring therapeutic use, all deserve some kind of sanction.

Sadly we may never know the real reason Valieva tested positive but we will all be witness to how the Olympic movement handles the case, and so far it is not looking good. The CAS decision is due Monday morning Beijing time. The world will be watching.

###

A Discussion with Dr. Don H. Catlin and Oliver Catlin

A Discussion with Dr. Don H. Catlin and Oliver Catlin

Mr. Catlin: We have worked on a number of cases over the years where supplements have been involved in a positive drug test in some fashion and have impacted careers or health. Athletes like

Mr. Catlin: We have worked on a number of cases over the years where supplements have been involved in a positive drug test in some fashion and have impacted careers or health. Athletes like

A

A  ailer has available for sale. Those interested in anti-doping and drugs in sport wonder how athletes manage to get their hands on banned doping agents to enhance their performance. One simple answer, products masquerading as dietary supplements on Amazon.com.

ailer has available for sale. Those interested in anti-doping and drugs in sport wonder how athletes manage to get their hands on banned doping agents to enhance their performance. One simple answer, products masquerading as dietary supplements on Amazon.com.

.

.  Unfortunately, an effective blood boosting drug in pill form is also the Holy Grail for endurance dopers. Though

Unfortunately, an effective blood boosting drug in pill form is also the Holy Grail for endurance dopers. Though  professional cyclist in the UCI Tour makes $142,000, according to Ernst & Young

professional cyclist in the UCI Tour makes $142,000, according to Ernst & Young