Russian doping has been at the forefront of people’s minds as the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games fade in our memories and we prepare for the 2022 Beijing Olympics to begin in February. The state-sponsored doping that culminated at the 2014 Sochi Olympics continues to cast shade over Russian sport–excuse me, the Russian Olympic Committee (ROC)–and indeed global competition, as the ensuing discussion and veiled accusations mar the Olympic spirit. But perhaps people should also be concerned about Russian doping of a different sort, one that is not often considered but should be. History has shown that athletes use Russian and Eastern European drugs as doping agents and yet few are prohibited today.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) Prohibited List outlines the substances that are banned in international competition including the Olympics. The 2021 WADA Prohibited List consists of 333 compounds listed by name, but the inclusion of catch-all language also prohibits related substances in many product categories. To be found, however, drugs have to rise to a level of concern and be targeted first and the WADA list primarily focuses on drugs of Western origin. Only four drugs of Russian or Eastern European origin appear to be included. Certainly there are others out there that would be attractive as doping agents.

Let’s take a look at the four drugs on the WADA Prohibited List that are of Russian or Eastern European origin and explore alternatives that athletes may be using today.

The story starts with bromantan, which was developed in the 1980s at the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences in Moscow. It can be found under the brand name Ladasten and is technically an actoprotector. Research out of Korea in 2012 explored bromantan in The Pharmacology of Actoprotectors: Practical Application for Improvement of Mental and Physical Performance. The writers described actoprotectors as “synthetic adaptogens with a significant capacity to improve physical performance.” The literature noted, “Bromantan was first found in an athlete sample at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics and was officially banned in 1997 as a stimulant.” There have been 11 adverse findings for bromantan in the WADA system since 2006.

Perhaps this is not surprising as a perfect alternative, bemitil, also known as metaprot, is described in the literature above and remains widely available online today, often at sites that offer Russian medicines or nootropics. The paper above explains that “nowadays, bemitil is manufactured in Ukraine (commercial name: Antihot) and is widely used in preparing Ukrainian national sport teams for international competitions.” It also notes, “Bemitil was successfully employed in preparing the athletes of the USSR’s national team for the 1980 Olympic Games held in Moscow.”

“Bemitil was successfully employed in preparing the athletes of the USSR’s national team for the 1980 Olympic Games held in Moscow.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3762282/

Bemitil was added to the WADA monitoring program list in 2018, 38 years after the Moscow Olympics you will note, but is not yet prohibited. If it does get prohibited, fear not there are alternatives for it, too. A site that sells Eastern European drugs like bemitil, MOSPharma.com, suggests four related products including noopept (see below) and trekrezan “from Russian pharmaceutical company Usolye-Siberian CPP,” with activity that “increases endurance during physical and mental stress.”

Next on the list of Russian doping agents is mescocarb, a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant and a dopamine reuptake inhibitor patented originally in Russia in 1970 by Vni Khim Farmatsevtichesky. Also known as Armesocarb, it is currently in clinical trials as an antiparkinsonian drug from Melior Pharmaceuticals. It has been sold under the brand name Sydnocarb with a nod to the technical chemical category in which it fits, mesoionic sydnone imine. Mesocarb does not appear to be widely available today online. It has been prohibited in sport since at least 1996 based on references to it at that time, but it has only been responsible for two adverse analytical findings since 2006.

There are also Russian alternatives to CNS stimulants with semax as one option. A poster on black market products with suspiciously doping relevant ingredients – annual report from the 2016 Manfred Donike Workshop discussed that semax “acts as a nootropic agent on the central nervous system and regulates dopamine and serotonine levels.” MOSPharma.com describes semax as “100% original from the Russian CJSC INPC Peptogen,” and notes it is used “to stimulate the central nervous system and enhance memory, focus, mental and physical performance, analytical skills.”

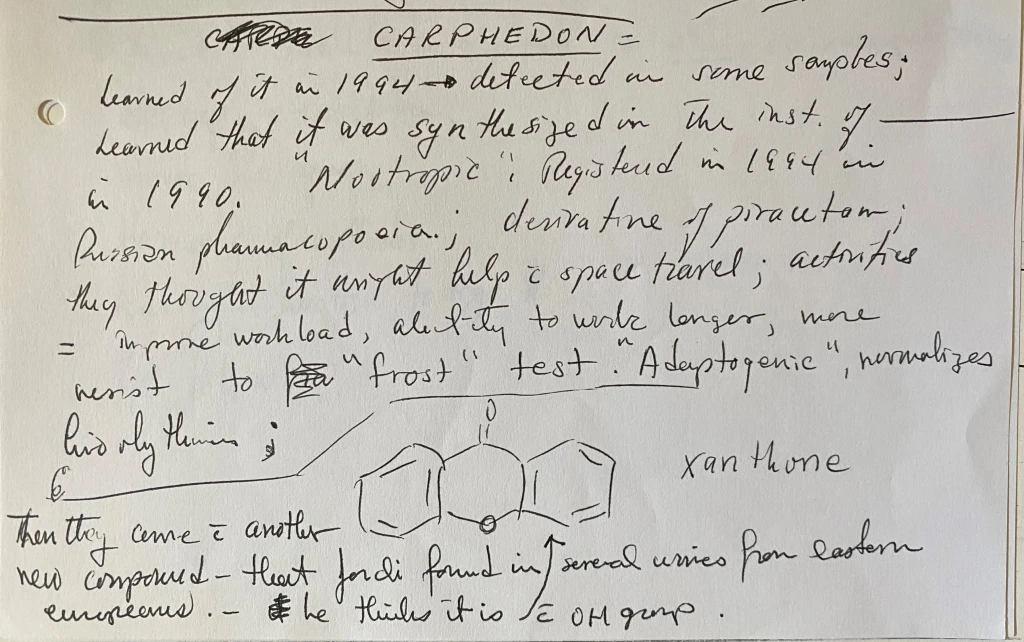

Carphedon, otherwise known as phenylpiracetam, is the next on our list and one of a family called racetams that are generally considered nootropic drugs. In 2019, researchers from the Czech Republic considered Carphedon at the Crossroads: A Dangerous Drug or a Promising Psychopharmaceutical? They explain this substance was “developed in Russia as a stimulant to keep astronauts awake on long missions, and occasionally used in Russia as a nootropic prescription for various types of neurological disease.” Carphedon “was synthesized in 1990 by Russian chemists as a combination of two drugs, nootropic piracetam and amphetamine stimulant.” A 2012 review of Piracetam and Piracetam-Like Drugs describes them as “modulators of cerebral functions,” used for, “various therapeutic interventions relating to the CNS, including (i) cognition/memory; (ii) epilepsy and seizure; (iii) neurodegenerative diseases; (iv) stroke/ischaemia; and (v) stress and anxiety.”

Handwritten notes from 1997 show carphedon was considered by my father, sports drug-testing guru Dr. Don H. Catlin, and colleagues at the IOC Medical Commission for addition to the prohibited list at the time. The notes describe carphedon as, “adaptogenic, registered in 1994 in Russian pharmacopeia that might help with space travel and improve workload.” The drug has caused 122 adverse analytical findings since 2006.

If you peruse the piracetam review highlighted above, you will find nine other racetam options that may be considered as doping agents. None is listed by WADA today. Neither is noopept, otherwise known as omberacetam, which has become one of the most popular nootropic agents on the market today. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) notes that “noopept was patented by Russian-based pharmaceutical company JSC LEKKO Pharmaceuticals in 1996.” The information cites that the “research shows Noopept has similar effects, but works differently than other nootropics in the racetam-family.” A number of sites compare the effects of phenylpiracetam to noopept with nootriment.com, suggesting that “both are purported to have benefits for memory, concentration, mood and alertness.”

From a banned substance standpoint, phenylpiracetam is on the WADA Prohibited List while noopept is not listed nor is it targeted. A synthetic drug, noopept, is widely available in supplement form despite it not qualifying as a dietary supplement ingredient according to the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA), which defines legal supplement ingredients in the U.S. It shows up in 32 dietary supplement products in the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements Dietary Supplement Label Database. In 2016 a BSCG blog post I wrote considered noopept could be the next big doping agent hiding in plain sight. That still remains the case today.

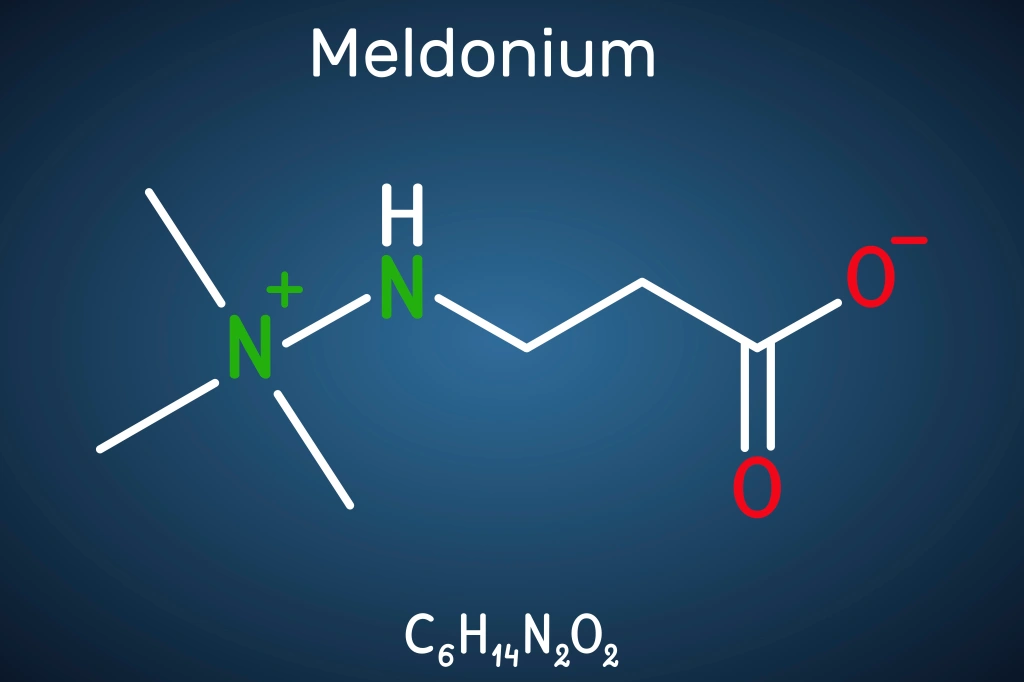

Last but not least of the four Russian doping agents is meldonium, otherwise known as mildronate. One will remember the maelstrom that ensued when meldonium was added to the WADA Prohibited List in 2016. There were 515 positive drug tests for meldonium in 2016, making it the most common substance found that year in Olympic sport. Tennis star Maria Sharapova was among them. There were 269 more positives from 2017 to 2019 for a total of 784. Meldonium is included on the WADA Prohibited List as a metabolic modulator in category S4.

Scientists from the University of Latvia and the Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis that created meldonium, described it as “an anti-ischemic drug.” Its performance-enhancing potential has been the subject of much debate likely because it is a complex substance that has a variety of effects. An excerpt from a 2005 paper written by the aforementioned scientists, Mildronate: An Antiischemic Drug for Neurological Indications, describes it as follows.

“Mildronate was designed to inhibit carnitine biosynthesis in order to prevent accumulation of cytotoxic intermediate products of fatty acid oxidation in ischemic tissues and to block this highly oxygen-consuming process. Mildronate is efficient in the treatment of heart ischemia and its consequences. Extensive evaluation of pharmacological activities of mildronate revealed its beneficial effect on cerebral circulation disorders and central nervous system (CNS) functions. The drug is used in neurological clinics for the treatment of brain circulation disorders. It appears to improve patients’ mood; they become more active, their motor dysfunction decreases, and asthenia, dizziness and nausea become less pronounced.”

The meldonium saga more than demonstrated athletes around the world had recognized an obscure anti-ischemia agent as a doping option and had started to use it. When it was prohibited, Russian scientists boasted they already had alternatives. As reported in USA Today from Moscow, “Federal Medical-Biological Agency head Vladimir Uiba says Russia has found ‘several drugs which are not banned and work significantly better than meldonium.’”

You don’t have to look far. Mexidol is broadly available on sites that cater to Russian medicine as well as on a site called DrDoping.com; very subtle. It is also available on Amazon from Pharmasoft at $21 for 50 tablets with a label that suggests it be used for “Anxiety Relief, Anti-Stress, and Ischemic Condition.” Mexidol, an anti-oxidant, was patented in 2002 in Russia with the patent describing the “invention relates to preparations used for prophylaxis and treatment of different forms of cardiac ischemia disease, atherosclerosis and acute circulation disturbances, cerebral insults.” With indications for ischemic conditions, it certainly appears similar to meldonium.

In a 2007 paper, Mexidol effects in extreme conditions, T.A. Varonina with the Institute of Pharmacology, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences notes, “Mexidol can be prescribed to humans to maintain efficiency in all kinds of extreme situations.” Could hundreds of Olympic athletes be using mexidol as an alternative to meldonium today?

A 2019 review from Russia of Pharmacoeconomic analysis of the neuroprotective medicines in the treatment of ischemic stroke compares mexidol to actovegin, which gained some notoriety as a potential doping agent around 2009 as explored in the Daily News. Actovegin, which DrDoping.com carries in pill form, is an extract from calf blood and is not on the WADA Prohibited List. In the article Olivier Rabin, WADA’s science director, suggests, “Actovegin could be used as a component of sophisticated blood doping methods, in which athletes withdraw, manipulate, and re-inject their blood to boost their endurance, or in conjunction with the use of erythropoietin, or EPO.”

When we ran independent drug-testing programs for several leading cycling teams in the peloton years ago, a key member of a team said to me after an event, “You know, Oliver, we aren’t doing anything that is over the line but we are doing everything we can up to the line.” That simple philosophy likely rings true across sport today.

People often ask if the Olympics or sport in general is clean today. To answer that simply, the system is very good at finding drugs that are currently defined as prohibited substances. None of the Russian or Eastern European drugs we note here–bemitil, trekrezan, semax, noopept and other racetams, actovegin, or mexidol–is on the WADA Prohibited List today. These Russian or Eastern European drugs certainly seem to be potential alternatives to prohibited drugs, but if they are not yet defined as such then using them is not yet considered doping. If sites like DrDoping.com has found them, who else might have them?

Oliver Catlin is the longtime president and co-founder of BSCG (Banned Substances Control Group), an international third-party certification and testing provider. With a background in sports anti-doping, he is widely regarded as a thought-leader in the field of sports nutrition and dietary supplements.

With the high-profile “Icarus” documentary now available on Netflix and in selected movie theaters, I wanted to take a moment to provide perspective on some points my father, anti-doping pioneer Dr. Don H. Catlin, and I have considered in regards to “Icarus” and Russian doping in general.

With the high-profile “Icarus” documentary now available on Netflix and in selected movie theaters, I wanted to take a moment to provide perspective on some points my father, anti-doping pioneer Dr. Don H. Catlin, and I have considered in regards to “Icarus” and Russian doping in general.