The Olympic doping scandal surrounding Kamila Valieva is one of the darkest moments the Olympic movement has ever faced. The system is struggling to contain the intense anger generated in all of the clean athletes that come to the Olympics and compete alongside others from around the world for glory. Sanctioned dopers are probably even angrier as they had to serve penalties while so far Valieva has not. Let the best athlete win and all is well. Allow a doping scandal to invade and all hell breaks loose. At the center of the scandal are cardiovascular drugs that can be used to enhance endurance; trimetazidine and hypoxen. One banned in sport, the other not. She also said she was using L-carnitine. Here we explore the substances used by Valieva, and others that could be alternative doping agents.

Valieva tested positive for the anti-ischemic drug trimetazidine (TMZ) on a Christmas Day drug test reported six weeks later causing the entire Olympics to take a collective pause. One hand on a team medal in figure skating for Russia and one hand in the cookie jar. Not good. Valieva also declared the use of hypoxen and L-carnitine on her collection form. All three have a common connection in that they are cardiovascular treatments or in some way impact heart function.

TMZ is not approved for use in the U.S. but it is commonly used as a heart treatment medication in Europe. From a doping perspective it can increase blood flow and improve endurance. A study done in Poland noted that TMZ could be found in relatively high amounts in treated wastewater demonstrating that it had become an environmental contaminant. This could expose crops irrigated with treated wastewater, or even animals that eat those crops, to the potential for contamination with TMZ. I wrote about this concern right as this scandal was breaking and the Olympics were doing a twizzle.

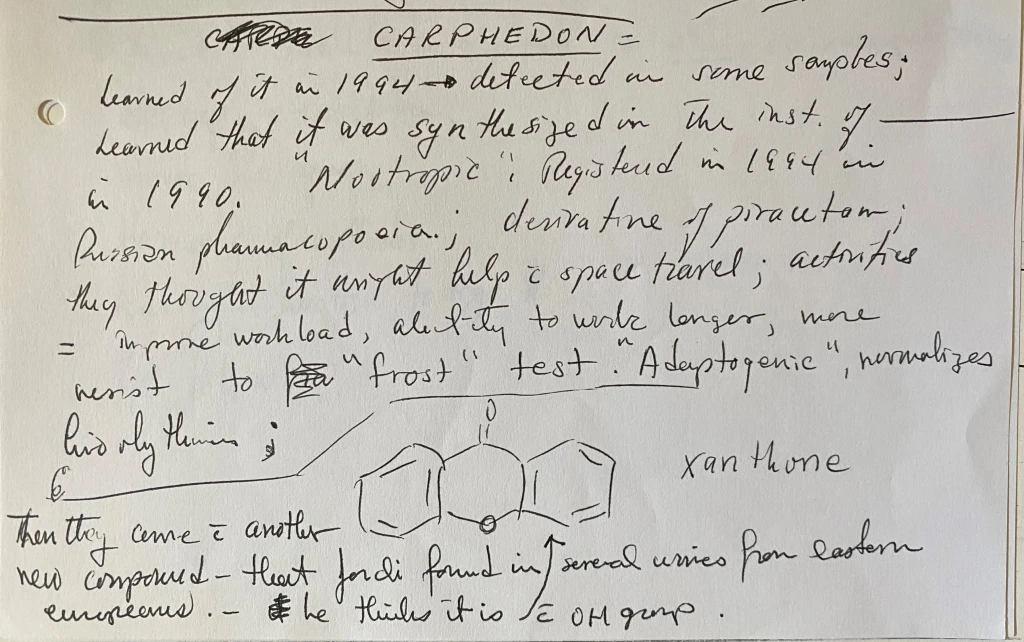

Realize that the now infamous drug meldonium is also an Eastern European anti-ischemic drug. Meldonium shocked the world in 2016 when it was first prohibited as it became the number one substance found in the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) system causing 515 failed drug tests across the globe. That number had dropped to around 70 by 2019 but it was still a common doping agent. The meldonium affair showed the world athletes were looking at anti-ischemic agents that were not yet prohibited as potential doping agents.

Trimetazidine itself was first prohibited in 2014. It was originally categorized as a stimulant and has since been moved to category S4 Hormone and Metabolic Modulators on the WADA Prohibited List. There have been an average of 9 positive drug tests each year for TMZ since 2014, not that many. However, “retrospective data mining regarding doping control analyses conducted between 1999 and 2013 at the Cologne Doping Control Laboratory concerning trimetazidine revealed a considerable prevalence of the drug particularly in endurance and strength sports accounting for up to 39 findings per year.” So it seems it was used a lot more before it was banned.

Trimetzidine sits alone as S4.4.4 right after S4.4.3 Meldonium. This is where anti-ischemic cardiovascular treatments that may have endurance benefits have been categorized on the WADA Prohibited List. Only a few examples of such drugs appear.

Hypoxen is one that does not, yet it is widely available at sites that cater to Russian pharmaceuticals. One such site has hypoxen as a ‘Cardiovascular Treatment’ along with 9 others that are not yet on the WADA Prohibited List. The summary of hypoxen on the site describes, “HYPOXEN is an antihypoxant and antioxidant. It reduces oxygen consumption and increase the efficiency of the organism in extreme situations, such as mental and physical stress, accompanied by a lack of oxygen,” it goes on to outline uses as, “To Improve Performance in Extreme Conditions (Including the Highlands, Arctic conditions, Underwater Work)” and, “Ischemia of the Heart Muscle (Angina Pectoris).”

A series of other options are on the site alongside TMZ, meldonium and hypoxen. The other options include Captopril (Capoten), Corvalol, Emoxypine, Riboxin (Inosine), VALIDOL (Validolum, Valofin, Menthoval, Menthyl isovalerate), VERAPAMIL (Isoptin, Calan).

Validol is of particular interest. The description outlines that Validol, “is an anxiolytic and produces a sedative effect as well as a moderate reflex and vascular dilative action,” under uses it includes, “Ischemia of the Heart Muscle (Angina Pectoris).” Let’s see increase in blood flow, anti-ischemic treatment. Sound familiar?

Riboxin is another substance I featured in an article in August 2021 on ‘Russian Doping of a Different Sort: Russian and Eastern European Drugs Hiding in Plain Sight as Alternative Doping Agents.’ The site that sells it notes several potential benefits to athletes including, “Provides anabolic effect,” and, “It reduces the area of necrosis and myocardial ischemia by improving microcirculation. Riboxin is also considered to improve muscle development.” Blood flow, ischemia. Check. This one even has anabolic effects. Ideal.

L-carnitine, the other substance Valieva declared, is a non-essential amino acid made in the human body that helps turn fat into energy. It is important to healthy brain and heart function and other processes in our bodies. Ingestion of L-carnitine is not prohibited in sport but injection over 50ml would be prohibited. L-carnitine injections in sport were made infamous by the Nike Oregon Project and Mo Farah, who admitted to the practice, then recounted in a mysterious saga reported by the Independent. In the Farah situation it was alleged that the amount injected was 13.5ml and not illegal. High amounts of L-carnitine when injected can enhance endurance.

Alberto Salazar, the coach at the center of the Nike Oregon project affair was excited about the potential of L-carnitine for performance enhancement. In a story reported by AP October 2, 2019 Salazar, “sent an email to none other than Lance Armstrong. ‘Lance, call me asap!’ Salazar wrote to the world’s most famous cyclist, who himself was only months away from being banned for life for doping. ‘We have tested it, and it’s amazing.’”

That’s the same stuff Valieva declared. Now, she may have declared an ingestible form of L-carnitine as a nutritional supplement, which would be perfectly legal in sport, or it could be this grey area high amount of L-carnitine injection practice in action. We just don’t know and we probably never will. It is sad to think that on top of everything else Valieva has suffered in this affair she could be a human pincushion as well.

These substances and practices are out in the open and appear to be obvious substitutes or alternatives for now notorious banned substances in sport like meldonium. Hypoxen, Validol, and Riboxin appear to be substances that would have clear doping potential. In the case of L-carnitine injections, it is a convenient workaround. It is time we open our eyes wider and address some of these potential doping agents as they are obviously in use.

This whole affair is an utter shame to anyone that loves the Olympics as I do. A 15-year’s doping scandal has cast a pall over the entire Olympics. Reduced to tears after her long program in Beijing, Valieva was clearly struggling under the weight of the scandal. Reporting in People noted Valieva’s coach was “heard admonishing her performance,” as if she needed more pain. Fellow Russian 17-year old Alexandra Trusova who won the silver was quoted saying, “everyone has a gold medal, everyone, but not me. I hate skating. I hate it. I hate this sport. I will never skate again. Never.” The gold medalist, Anna Shcherbakova looked shocked and stunned after winning. That is the kind of unbelievable pressure these Russian girls are under. Meanwhile the bronze medalist from Japan cried tears of joy.

Olympians are supposed to have the opportunity to come together alongside the best of their kind in the world to celebrate camaraderie and their unbelievable dedication to sport while proudly representing their countries in hopes of basking in Olympic glory and maybe winning a medal. Instead Valieva has to answer for the failure of the Russian system to evolve the culture to one that actually endorses clean sport. Worse yet she has to answer for the failure of the Olympic movement to manage it. So too do all the other athletes crushed by the latest Russian doping scandal. The last four Olympics have been marred by talks of Russian doping. It is about time that ends.